‘Artifice, (Ripped)’

BOMB FACTORY COVENT GARDEN, 99-103 LONG ACRE, WC2E 9NR

I met Tarzan last week. In his basement studio right by Covent Garden, he told me a

story about descending into a graphite mine in Sri Lanka. Surrounded by artefacts

from this story he had constructed, pseudo-souvenirs if you will, I waited to find out

what he might have found in the mine. Clearly he’d been looking for something -

everyone who writes a story is in a way seeking, as much as they are telling. Through

the process of laying pen to paper (or more likely fingertip to plastic key), a story

uncoils and tries to produce something more than its constituent parts.

In the end, there was nothing at the bottom of the mine shaft. No revelation, no cigar.

There’s a lot to be said for looking for something and not finding it, for expecting a

thing to be more than itself. The theme of that burgeoning hope being axed by the

frankness of materiality is present throughout the works in the exhibition. ‘Artifice,

(Ripped)’ brings together four artists to investigate how we remember through

artefacts and texts. There are two stories that guide the narrative of the exhibition -

one taking place thousands of miles above sea level, the other hundreds of meters

below the earth’s surface. Tarzan KingoftheJungle writes about his experiences in

the mines, whilst Won-Joon Choi narrates his experience of getting lost in the Alps.

Neither story sticks too tightly to the truth, taking liberties in the style of Chinese

whispers, warping and unfixed. Tom Hardwick-Allan sculpts crows which act as a

medium between the two, portents of death for situations that could easily have

gone awry, but didn’t. Made out of empty beer bottles, gutted in the artist’s studio

and presented in upturned corner shop bags with the simple gesture of pinching one

corner into a beak to differentiate between realities. Panos Profitis has sculpted the

goats Choi claims he met on the mountain in his story, only Profitis hadn’t read Won’s

story before making the pieces. The curator has brought them together because

they can act as a visual aid, a false artefact, hailing from Greece - not the Alps.

This is fitting for an exhibition about the tendency to apply a false paradigm onto

experience, to project onto it more than it is, or can be.

It deserves to be said that the mine Tarzan discusses is actually more than it might

appear. The Sakura mine was the biggest producer of graphite in Sri Lanka until the

second world war, and boasts some of the purest and most dense graphite veins in

the world. Similarly, the Alps, crows, and mountain goats hold their own prowess and

mystery, distinct and independent from our engagement with them. The exhibition

demonstrates our continuous attempts to preserve through distillation be it in

sculpture, painting, poem, story - we know that we are doomed to fail, and that the

end result will necessarily be an artifice, but that never dissuades us from trying.

Text by Maria Dragoi

List of Works

Clockwise from entrance:

‘Crows’, 2018 - 2023, Tom Hardwick-Allan

Corner shop bags, empty beer bottles

‘Fruitless Descent’, 2022, Tarzan Kingofthejungle

Looping moving image installation, played on four monitors

‘Macguffin 1 (lantern)’, 2023, Tarzan Kingofthejungle

Battery lantern, fake ice, sand, glitter, scrabble tiles

‘Vertebra (failure)’, 2022, Tarzan Kingofthejungle

Plaster, sand, glitter, scrabble tiles

‘Park’, 2022, Won-Joon Choi

Print on paper

‘Park II’, 2022, Won-Joon Choi

Print on canvas

‘Park III’, 2022, Won-Joon Choi

Print on paper

‘Macguffin 2 (bottle)’, 2023, Tarzan Kingofthejungle

Bottle of Evian, fake ice, sand, glitter, scrabble pieces

‘Ode’, 2020, Panos Profitis

Polyester and Calcium Carbonate

‘Vertebra (rapture)’, 2022, Tarzan Kingofthejungle

Plaster, sand, glitter, scrabble tiles

‘Winspit (Banquet)’, 2023, Tarzan Kingofthejungle

Giclée print on Hahnemühle German Etching paper, timber

tray frame

‘Winspit (Knights)’, 2023, Tarzan Kingofthejungle

Giclée print on Hahnemühle German Etching paper, timber

tray frame

‘Macguffin 3 (book)’ 2023, Tarzan Kingofthejungle

‘The Singularity is Near’ - Ray Kurzweil, fake ice, sand, glitter,

scrabble tiles

Accompanying texts by Won-Joon Choi and Tarzan Kingofthejungle

Tarzan’s Story

About a year ago I got to know a man called Jimmy. He gave me an idea; the inadvertent planting of a seed that took root and grew over the course of the next year, a burgeoning demand, aching to flourish. Jimmy would have heated Scrabble games with his friends, that I pretended not to eavesdrop on, and come into the kitchen for a cigarette break still raging at team mates. In these brief chats, I listened intently to anything and everything he had to say. He always spoke eloquently, with an uncompromsing choice of slick, unconventional words. Words plucked from a brain bulging with memorised quotes, digested, analysed, and ready to regurgitate. I would offer up ambiguous questions to pass the time, to get Jimmy regurgitating. And he would counter-attack with strange, albeit considered, answers. When asked how he would choose to die, Jimmy responded: “Butt-fucked by a Rhino” within a millisecond of thinking time, as if he’d thought about it in depth before. I never asked why that would be his choice of death. I didn’t need to know why. Perhaps over-analysing his strange answers and sayings would detract from the mystery. During one scrabble game’s smoke-break, when asked where his dream place to live would be, Jimmy replied with an answer that left me... befuddled. (67 Points). Again without missing a beat, he answered “Underground”. He went on to describe the space with harsh and pejorative language but added complimentary adjectives as if to glorify the uninviting abode. My interest was piqued when he spoke of “the realness of being down there in the dirt.” These words repeated in my head like a tape echo, slowing slightly each repetition. “Reeealnesss.”...“In the diiiiirt.”. Get Ready for a 70 pointer.. Unbeknownst to me at the time, he would leave the country for good later that year. A rash decision following an argument over a particularly heated game of scrabble. He was gone. Just like that. However, some of his words would stay.

It was eight months later that I met a man called Mamu. When we met, I was unaware of his unofficial title: Village Badass. He lived in the village of Akurala in southern Sri Lanka, where we would share a bottle of coconut arrack in the evenings. After a few drinks, Mamu would become animated and tell incredible stories. He was in his late sixties and had gained that reflective status one can only claim with age and a life well-lived. He spoke about tsunamis, machete fights with perverts and crocodiles eating neighbours. I think these stories earned him his title. At first, I took a lot of what he said with a pinch of salt. One night Mamu told me about the Himalayan eagles that “fly down to the ocean and eat floating whale shit.”. He went on to explain that the eagles are hated by the local fishermen as they too are trying to find the whale shit, to sell to perfumeries for millions of rupees. I, of course, doubted this was all true but sure enough a few days later Mamu came over and dropped a newspaper on the table in front of me with a wide grin on his face. The paper was in the local language of Sinhalese, which I could not read, but there were pictures of an eagle, a washed-up dead whale and some floating faecal-looking matter. Mamu pointed at the pictures saying “look look, no lie, I say truth”. I believed everything Mamu said after that and when he mentioned his friend who worked underground mining moonstones, to sell to deluded hippy travellers, my interested was piqued again. The next day Mamu and I drove to his friend’s mine and we climbed down. It was not as deep as I’d expected, and I could see the surface from the bottom. Jimmy’s exact words were still lingering in my head, and the idealised image I had conjured up of the ‘underground’ was far from the glorified mud-pit I was stood in. I did, however, get talking to another local man called Tuti about the other mines in Sri Lanka, the graphite mines. Tuti introduced me to a man called Chandika, who had a friend called Mr. Kaypee, who worked at Sakura graphite mine, owned by someone called Mr. Jaytrala. Three trains, two busses and a Tuk Tuk ride later, I found myself at a large pair of iron gates, half way up a mountain, 75 Miles North of the Capital, Colombo. A security man, called Kufi, took me to meet the owner, Mr. Jaytrala, who took me to meet his technician. (whose name I can’t remember but he looked a lot like Andrew Garfield). He found me some steel-toe cap boots, a helmet and a torch. And there began my fruitless descent.

I had to sign a hand-written form, accepting responsibility for my own safety in the event of an earthquake. It wasn’t until after I had signed it that Mr, Jaytrala asked me why I wanted to go down. And it wasn’t until after he asked this, that I even questioned my own motives. I wanted to go down. Why, I wasn’t sure. It felt right, as if somehow everything had been leading up to this venture. The chance happenings, meetings and conversations acted as catalysts, not by chance, but by design. I started to feel as if something important was going to happen down there. Something I could not translate to Mr. Jaytrala. He was still waiting for an answer. “To film?” I replied with a lack of conviction that, I think, worried Mr. Jaytrala. He did not join me on my descent. He handed me over to one of the technicians, (Andrew Garfield), to show me around.

The mining process was convoluted. Drilling, charging, blasting, extracting, transporting, sorting, grinding, storing, sieving, drying, packing, exporting, processing, importing, re-packing, pricing, stacking, unloading, selling, unpacking, cleaning, heating, shipping, checking, loading, tracking, re-cleaning, producing, labelling, moving. Regurgitating.

At the bottom of the mine I found myself with no English speakers, and halfway through a badly performed charade of “very cold down here”, I realised ho little words mattered in this situation I’d found myself in. No words were of any use to me. We were exchanging empty sounds, robbed of their intrinsic value. I wondered what the other miners thought of me. As a tourist? An anomaly? A new recruit? The miners seemed to enjoy the disruption to their normal day’s work. I started to wonder what would happen to us in the event of an earthquake. There would probably be a loud crash followed by screams, echoing down the tunnels as the walls caved in. Water would begin spewing out from the cracks in the walls and the electricity supply would fail. As darkness set in it would dawn on us that we were stuck down there. Words would still mean nothing, deeming us humans equally inept. The rock would loose it’s value too, and we’d all be the same; excess material in a submerged air pocket. I thought about this for a while as I became less aware of my surroundings, slipping into a daydream. Hundreds of meters below the earth’s surface, recording grainy iPhone footage, waiting for something significant or important to happen, I thought of my friend Piers. Piers talks about us being ants in an ant nest; he says “if an ant loses a leg, no one cares.” The other ants carry on working, then they die and are replaced.

I think he uses this metaphor as a reassurance that nothing really matters, but it does the opposite for me. I thought about his metaphor for a while. I considered the importance of a singular ant when thinking about the colony as a multi- cellular organism. An animal, with roles filled like cogs in a machine, and the queen at the centre. The control room. Her brain, the nucleus. She will eventually die and be devoured by her offspring. And when this happens the death of the colony will not be immediate, it will die off slowly as no new members are added.

The lower I got, the darker it became, but the graphite coated everything in a layer of reflective dust, resembling a clear, starry night-sky. I wanted for something to click into place, coating everything in a layer of significance, so that it all made sense. As I tried my hardest to forge an artefact from this experience, to be fetishised further down the line, my optimism began to run out, and it dawned on me that maybe nothing out of the ordinary was on schedule for today. I thought about the mine itself, a perfect physical representation of the process of spiralling down, deep under the surface, of face-value information. Every level a new consideration. Analysing, digging further and sifting through non-sensical, no- value waste material, to eventually find.. more rock. Rock worth something. Rock of importance. I thought about the thousand-year processes at play, separating one type of rock from another. I pictured the miners as neurons extracting the valuable information from the unwanted waste and extra data, carrying it to the cart, pushing it back along the dredged tunnels to the main shaft, chains lifting the extracted rock up the levels, past rumbling machinery and abandoned tunnels. The graphite twinkles in the sunlight as it surfaces.

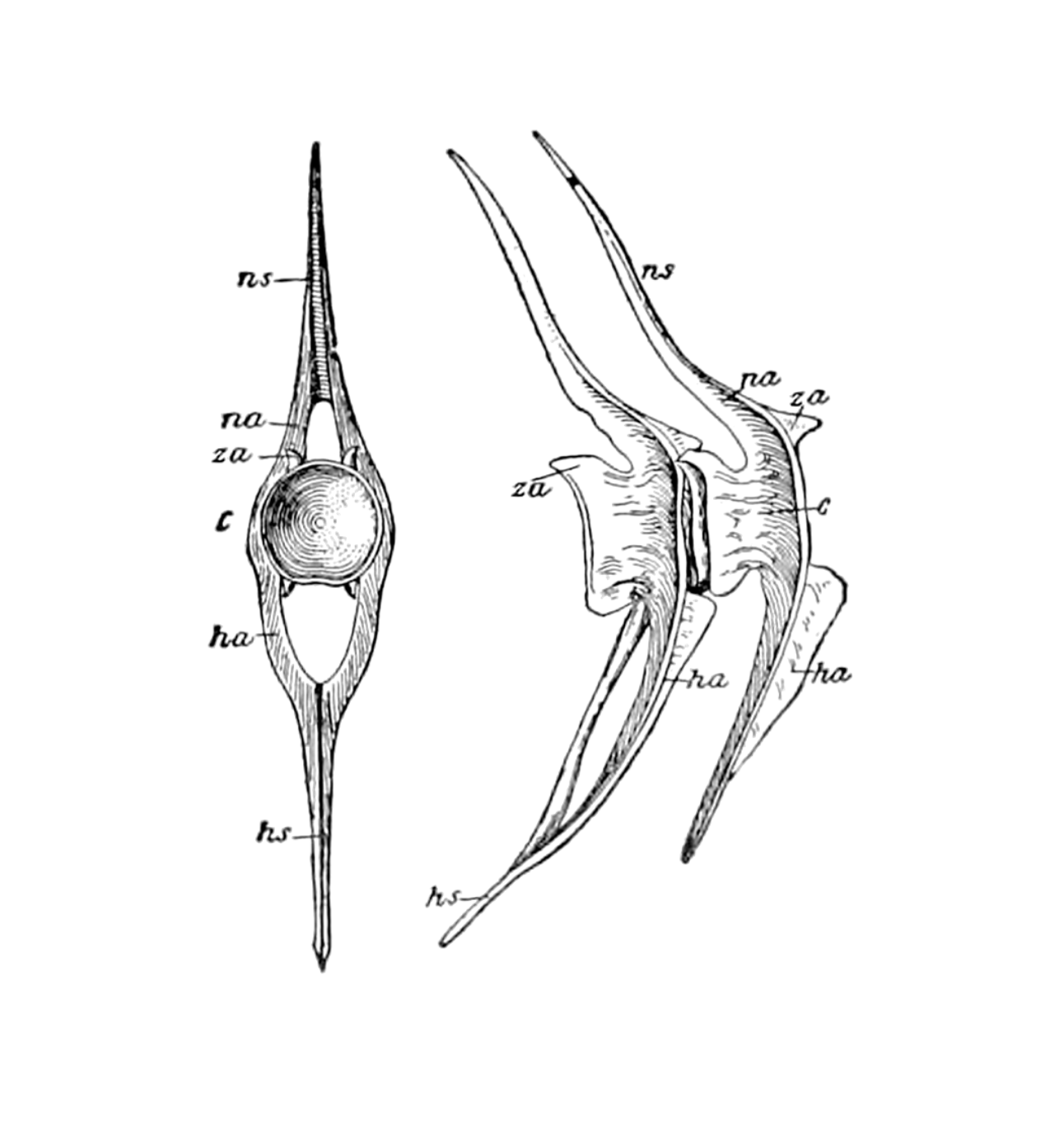

And then, still pining for an occurrence that would resonate, the universe offered up a nod to its own predictability. I felt a sharp pain as something dug into my upper thigh. I felt, through my shorts, a peculiar shape. I reached into my pocket and pulled out a bone. I had forgotten about it. It must have been in there for about ten days. I had picked it up on the beach. I had pocketed it for no other reason other than I just liked the shape. I think it was a vertebra from the neural spine of a fish. I was reminded of an old Khmer proverb that Mamu had told me: When the water rises, the fish eats the ant, when the water recedes, the ant eats the fish. I don’t think I understand what it means. I held the bone in my hand, studied it for a while. The sound of my fingers rubbing along its porous surface took precedence over the various sounds of machinery that congealed into a distant hum. The soot and grime covering the floor and walls faded from my attention. This gleaming bone took priority. Absolute symmetry. A smooth, matt- finish. Truly perfected craftsmanship.